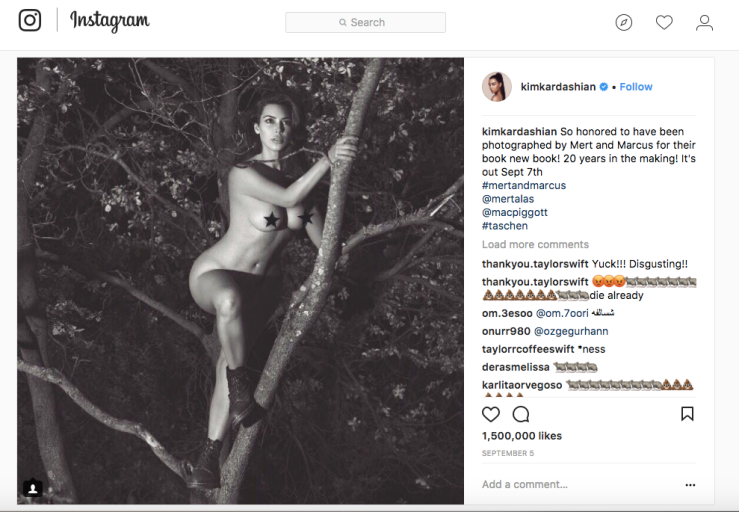

Kim Kardashian is naked on Instagram – again.

This in itself is not shocking. Having built a commercial empire on little more than her image, the reality star is no stranger to nudity, especially on social media. Yet everything about one particular picture, released in September 2017 by celebrity photographer Mert Atlas is striking, especially for the New York School acolytes among us.

Posed climbing a tree, Kardashian looks out toward the distance, courting our gaze but refusing to meet it. Shadows and stars obscure parts of her famous form (likely to appease Instagram’s sexist policies), but her body is fully displayed. The thing I find remarkable about the shot, however, is not what she’s taken off, but what she’s left on.

Here is, improbably, Kim Kardashian: nude with boots.

Depicted in nothing but her boots, Kim’s picture uncannily evokes Larry River’s famous 1954 portrait of Frank O’Hara. Created over sixty years apart, each “Nude with Boots” portrait embodies its own moment in cultural history, yet they together reveal how a politics of exposure and vulnerability, inseparable from questions of gender and sexuality, is always subject to aesthetic (re)appropriation. An unlikely connection between a gay mid-century poet and 21st century TV icon soon begins to seem the most natural thing in the world.

In some ways, their connection is even instinctive. Though not uncritical (as Andrew Epstein has made clear), O’Hara’s poetry virtually sanctifies the celebrity culture of his day. In one of many rapturous poems about the cinema, “To the Film Industry in Crisis,” he proclaims: “but you, Motion Picture Industry, it’s you I love,” heralding Mae West, “in a furry sled, her bordello radiance and bland remarks,” Marilyn Monroe “in her little spike heels” and the inimitable Elizabeth Taylor (among several other male and female stars). “Long may you illuminate space with your marvelous appearances,” he intones,

and may the money of the world glitteringly

cover you

as you rest after a long day under the kleig lights with your faces

in packs for our edification…

Replace “Mae West” or “Elizabeth Taylor” with “Kim Kardashian” and “under the kleig lights” with “on television cameras” and O’Hara’s poem might well speak to our reality zeitgeist instead of to the dazzling display of cinemascope. I like to think that, were he alive today, O’Hara might be thrilled to see Kardashian, ultimate celebrity symbol – she, too, of “bordello radiance and bland remarks” – depicted so like himself. Perhaps he would write a poem for her, much as he did for James Dean, Lana Turner, and Billie Holiday.

Today, O’Hara has no doubt become something of a celebrity himself, both through critical lore and his indelible internet presence. Still, his connection to Kardashian seems forged not just on the basis of this celebrity, but on a certain sense of cause célèbre.

Upon its debut, Rivers’ portrait was controversial for its shameless portrayal of the nude male form and bold implication of homosexuality (or, at least, homoeroticism) in a repressive McCarthyist era. As poet Eileen Myles noted in a recent discussion: “The thing that’s outrageous about [the portrait], continually, is that O’Hara’s male…” By presenting us with a nude male form rather than the traditional female subject and by divulging private intimacy in public – “like an announcement that [the two artists] had sex” – the portrait doubly violates artistic and social propriety.

For her own part, Kardashian is certainly familiar with prurient scandal. Cultural consciousness surrounding the star has long been shaped around narratives of her sexuality, both those (perhaps unfairly) imposed upon her and those she seeks to articulate on her own terms. As she wrote in a 2016 International Women’s Day blog post: “I am empowered by my body. I am empowered by my sexuality. I am empowered by being comfortable in my skin….The body-shaming and slut-shaming – it’s like enough is enough. I will not live my life dictated by the issues you have with my sexuality…”

Many were quick to deride her conflation of nudity with empowerment, but of course, she can’t win. The routine disapprobation of Kardashian as a public figure often seems to say less about the star herself than it does about the troubling ways our culture treats women: objectify, dehumanize, blame. Much as O’Hara’s nude form might have in the 1950s, Kardashian’s contemporary image stokes our most deeply engrained societal fears of and desires to control female (and Other) bodies. And, like it or not – like her or not – she continually refuses that censure, one nude portrait at a time.

This is what her nude-with-boots likeness and O’Hara’s portrait, I think, hold most deeply in common. In Rivers’ painting, as Brian Glavey maintains, O’Hara is “made in an image – and made into an image.” The latter formulation is crucial, for O’Hara is not just passively depicted but actively co-conspires to create his image. His poetry functions in much the same way; as Nick Selby has surmised: “any reading of O’Hara cannot escape the implication that his selfhood is a carefully choreographed textual performance, light and sassy, knowing we are looking.”

Consider, then, Aimee Cliff’s shrewd assessment of Kardashian:

[She’s] a woman who controls the production of her own image in a world that consistently tries to steal that right from her. That’s unequivocally empowering.

Kardashian has cracked the code of how to be private in public. Particularly as a woman, and a woman whose body has been violated by millions of eyes, she is someone for whom this is an important triumph: she stands before a world that wants to see every detail of her, and to demean and devalue her by doing so, and somehow manages to cash in on the former while putting off the latter.

How do you control your body, your image, your very sense of selfhood in a society where it is always under siege?

You put on your boots and go on the defensive. You expose yourself before they can, wresting back the power to control your detection. You make them look. You turn it into art.

Glavey notes that O’Hara’s “embrace of visibility” is an “important revision of the normative notion of masculinity” that make “homoerotic representations of the male body…unthinkable.” So, too, does Kardashian’s “embrace of visibility” revise normative notions of femininity – modesty, chastity, deference – long used to subordinate women. In fact, upon the release of his 2014 selfie book, Selfish, the poet Sam Riviere (who providently devoted an entire book of poetry to her) lauded Kardashian as “a feminist artist for our time,” remarking how,

Inextricably connected to Kardashian’s command of her image is the history of male ownership of images of woman: through the history of western art, the “muse” tradition, and the sanctity of male artistic genius. It’s hard to avoid the feeling that those who criticise the “vanity” of young women who create and publish images of themselves online are simply reinforcing the age-old male control of female representation, and calling on harmful myths of shame and propriety to do so.

Her nude portrait consecrates this understanding, presenting her as powerful, self-possessed, and fully in control. And at a watershed moment when women are rising to declare #MeToo, this defiance of hegemonic narratives (rendered visually, verbally, or otherwise) has never had so much cultural purchase.

I have always thought that the power of Rivers’ portrait derives not from O’Hara’s aggressively open stance or his startlingly exposed penis but from the boots themselves: their militaristic implication and sense of sheer endurance. Sure they’re practical, especially if, like Kim, you’re climbing a tree. Then again, maybe she’s not climbing at all – maybe she’s poised to knock the whole thing down.

As Eileen Myles argues, the boots depict a sense of readiness: they “mean that you can run.” This reading echoes O’Hara’s cheeky manifesto Personism, in which he is clear that “If someone’s chasing you down the street with a knife,” you don’t engage, “you just run.” Yet I suggest that the portraits imply less a readiness for flight than a readiness to stand one’s ground. If the exposure of homosexual and female bodies always holds potential for violence and violation – a terrifying possibility that became all too real when Kardashian was robbed at gunpoint and that O’Hara himself well knew– their images, nude with boots, affirm the corporeal sovereignty others seek to deny.

Nude with boots, these portraits exude a certain spectacular fearlessness. Together they offer not just a provocation but an occasion for visual and visceral celebration – as O’Hara has it in his aptly titled poem “River” – “upon the open flesh of the world.”

Alexandra J. Gold

Alexandra J. Gold is a PhD Candidate in English at Boston University, where she will (very soon!) be defending her dissertation on the connections between the visual and verbal arts in Frank O’Hara’s and Robert Creeley’s poetry. She is beginning work on a book, “Reckless, Beautiful Things: Contemporary American Poetry and the Artists’ Book,” that will consider collaborative projects by O’Hara, Creeley, Anne Waldman, and Mei-mei Berssenbrugge. Her love of the New York School is perhaps only rivaled by her love – in true O’Hara fashion – of pop culture and reality television.

1 thought on “On Seeing Kim Kardashian’s Naked Portrait (not at the Museum of Modern Art)”